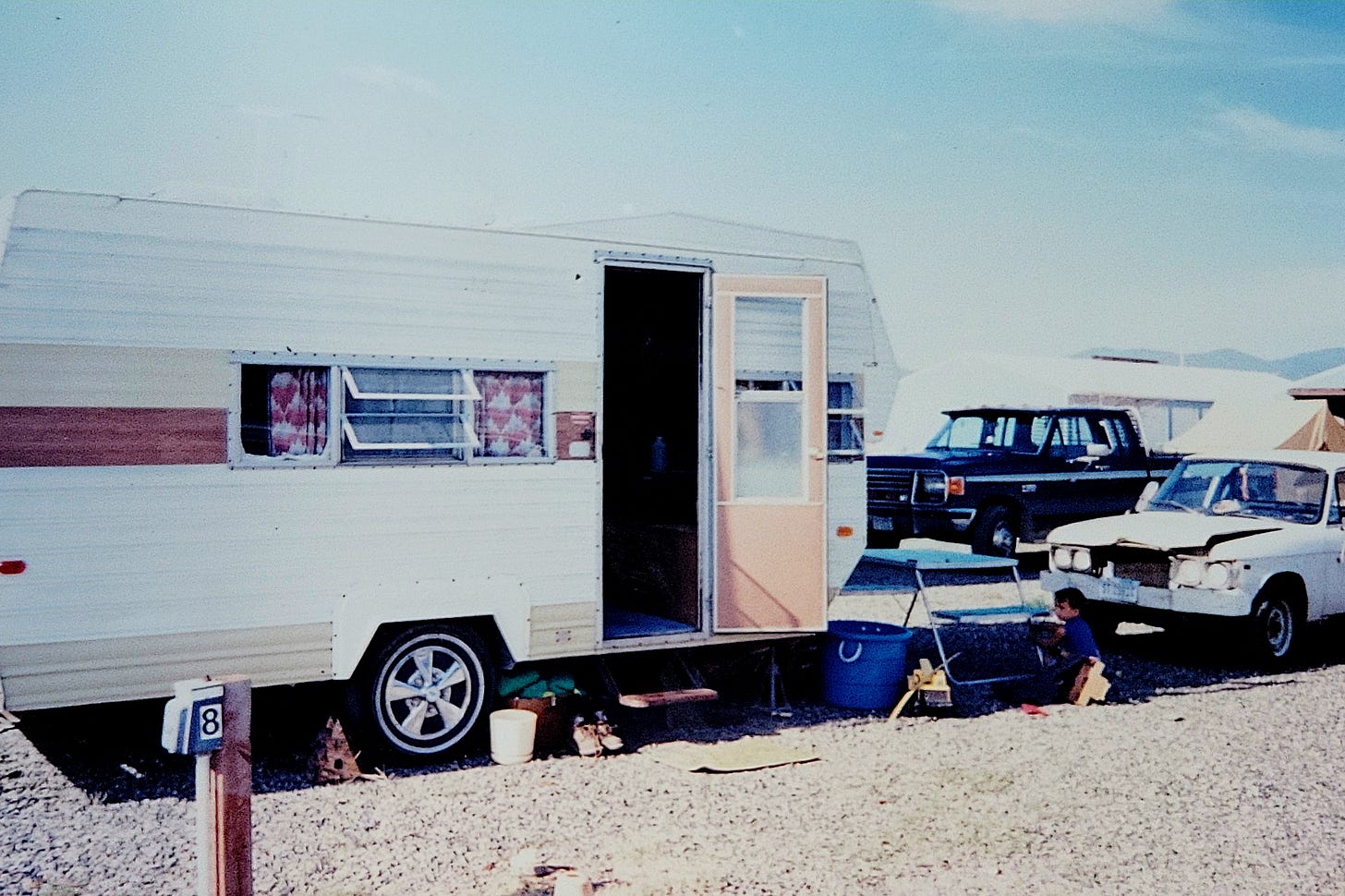

During the summer of 1994, I lived in an old 14-foot travel trailer with my three-year-old son. The quarters were tight, but we framed it as our Summer Adventure. Three year olds are pretty adaptable.

A requirement of the Natural Resources program I was attending was that I work a season in the field before my final year of college. As an unemployed 23-year-old single parent, I could only attend a Community College because of a Pell Grant and a childcare stipend awarded by the federal government.

Even with that assistance, I took out additional student loans to help buy diapers, winter coats, vehicle tires, and gas to get to school, daycare, and back home each day. These tax-payer funded social resources made college possible1, and college gave us the possibility of a better future.

After many hours of filling out job applications, I accepted a position as a Forestry Technician for the US Forest Service.

The day came when I finished my last classes of Spring Quarter and, exhilarated, headed to Montana in my ‘71 Chevy Luv pickup. My grandfather followed, towing my trailer to the RV space I’d reserved 320 miles away. Late that night, just five miles from my destination, a deer jumped in front of my truck. I couldn’t avoid hitting it. The impact shattered my hood and split my radiator. Not a great start.

A few days later I learned I’d work on a trail crew of two, my crew boss and I responsible for maintaining the majority of trails in our ranger district2. We logged out trees and shrubs using chainsaws and crosscut saws, and rebuilt structures like bridges, signage, water bars and retaining walls all while carrying everything we needed to do the job on our backs.

The position required us to camp in the back-country for multiple nights every other week to clear trails that couldn’t be accessed on a day hike, while on the alternating weeks we cleared smaller in-and-out day hike trails.

I hiked more than 200 miles that summer.

We divided the work of carrying the load. Depending on the trail we were heading to, we might bring hand tools, crosscut saws, pole saws, chainsaws, Dolmars3, and replacement pressure-treated sign posts, along with water and concrete mix. In addition, we carried our water, safety gear, and food. On overnight hikes, we brought additional clothing, bedding, food, and tents. Whether a day hike or a week-long pack-out, the loads were heavy—I had never worked that hard in my life.

My Red Wing leather logger boots were brand new the day I started the job—a rookie mistake. I learned too late that they needed to be broken in slowly. By the end of that first day, I had deep, raw blisters bleeding through both of my socks, wounds that lasted the entire summer. At night, I peeled off my socks with shaking hands, the fabric stiff with dried blood and layers of shed skin. Some mornings, I laced my boots while biting the inside of my cheek so I wouldn’t groan and wake the other campers with those painful first steps.

It was a grueling summer. Some days we hiked eighteen miles through gentle terrain. On other days, we moved three miles in eight hours, climbing over blow-down obstructing the trail, each step a puzzle of sweat, balance, and persistence.

I wasn’t in good physical shape. I wasn’t an athlete. I was a smoker hauling 40 to 75 pounds on my back, trying to keep pace with a seasoned crew boss.

“I can’t do this.” The thought hit me often, usually halfway up some brutal climb, lungs burning, legs shaking, heels hurting. But I never stopped. I had a job to do and a son waiting for me back home.

The scars on my heels are minor compared to ones I carried into that summer—invisible wounds formed by abandonment, abuse, and a childhood I was trying to outrun. I had traded one pair of boots for another: the Red Wings replacing the oversized cowboy boots I wore the day my mother left my brother and I on the doorstep of the welfare office when I was four (her attempt to save us from a life of domestic violence). Both pairs rubbed me raw in their own way—but the new scars came with new found strength.

Somewhere between the sting of sweat in my eyes and the solitude of my thoughts, something shifted. I stopped checking how many miles were left. I kept going.

I found my way in nature. Learning to be cautious around a cow moose and her calf in a quiet meadow reminded me of how strongly I wanted to protect my own son. The wildflowers growing back after a burn showed me that recovery was possible—that something good could grow, even after hard times. The call of a bull elk in the late summer, deep and echoing, stirred a yearning to live that I hadn’t known I possessed.

Out there among the hills and the trees, I started to become the person I was meant to be.

Thirty years later, I still have the Red Wing boots. The leather, worn and gouged with scratches, is long overdue for a good oiling. Silver eyelets still hold the original braided laces, the ends frayed from decades of tying and untying. My boots fit like a glove and are still my preferred shoes for hiking.

That summer didn’t fix everything. Life didn’t suddenly get easier. There were more hard seasons ahead—degrees to finish, jobs to work, children to raise, marriages that came and went and came again. But that summer gave me something real to hold on to.

It was the beginning of my belief that I could have a new life—one step at a time, even uphill, even with blisters, even when the worst wounds were the ones I couldn’t see. It taught me that self-reliance isn’t about having all the answers; it’s about staying on your feet, even when they hurt like hell. I had proof that I could do hard things, even when I was tired, uncertain, and on my own. My boots, purchased so long ago, are a solid reminder of where I came from.

Sometimes, strength looks like a pair of well-worn leather boots.

Do you know what small acts make huge impact to me and my writing? Subscribing for a free weekly essay; taking a minute to leave a comment and/or provide feedback; clicking the ♥ (like) and restacking (if you use the Substack app); and by sharing it with others via email and/or social media. These small things help keep me inspired to keep writing.

On tax payer funded social programs: I have since paid back those student loans and contributed my share in taxes as a ‘hardworking American.’ I firmly support my tax dollars funding social programs and will never judge another who utilizes those resources to improve their future.

On the USDA Forest Service Agency Organization: There are more than 600 United States Forest Service Ranger Districts in the US. https://www.fs.usda.gov/about-agency/organization

You are a superhero. ✌️ ❤️ 🐧

Beautiful and intriguing. How perfectly you!